Photo Source: New York Times

Are you happy?

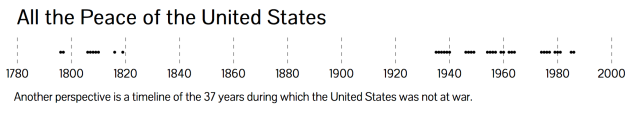

What seems like a simple question can actually provoke one to reflect on their entire life. The question of whether someone is happy or not can actually be interpreted in a multitude of ways and can also be reflective of someone’s mental state, thoughts, or feelings at the time of inquiry. For instance, some people may interpret the inquiry into their own happiness as a general act of courtesy similar to passing a stranger on the street and saying “how are you,” in which the standard answer would be “good, how about you?” Others may interpret the question as a request into one’s thoughts in which they willingly open up their genuine feelings to the person asking. Considering the implications of asking someone whether or not they are happy in life, what business does someone have in asking this question to a total stranger? Even more interestingly, what business do nuns have in regard to asking this question? In the 1968 film “Inquiring Nuns,” Sisters Marie Arné and Mary Campion sought to do just that by asking strangers on the streets of Chicago if they were happy. Sister Arné and Sister Campion’s inquiry experiment garnered a mix of reactions, but the strangest of them all when compared to American culture in 2018 was the willingness of the subjects to provide the nuns with an answer.

The film began with the two sisters in a car in which they traveled down what could be presumed to be Lake Shore Drive on their way to inquire into strangers’ minds in downtown Chicago. On their way downtown, the cameraman began the process and told them what they were to do and the sisters responded with any questions they had such as how to go about introducing the question to the stranger. The question-asking at the beginning demonstrated just how unplanned and spontaneous the so-called “experiment” was to be. The sisters seemed somewhat confused on how to go about inquiring into the happiness of a stranger, which made visible the complexity hidden behind a single question, and even more, the complexity of human emotions.

As the sisters began their experiment and asked multiple strangers whether they were happy or not, it seemed as though a common theme was that the strangers would answer the question first, and then ask what the film was for. Answering the question first and then asking what it was for is interesting when considering the tendencies of people today. Nowadays, if someone were to ask a stranger a question, especially on camera, they would ask what it was for first, then contemplate answering the question. Asking and then answering on the interviewees side could possibly demonstrate an increased lack of initial trust in a stranger in the modern age compared to in the 1960s.

By comparison, it seems as if the world in 2018 is more troubled and that someone is more likely to be put into danger at any moment, unlike in the 1960s. However, the perception of increased danger could simply be because of an increased accessibility to news, rather than an actual increase in crime because crime rates were higher in Chicago in 1967 than in 2018.

Photo Sources: Chicago Tribune (Historic) (Left), Chicago Police Department (right)

According to the pictures above, Chicago experienced far more crimes within one month in 1967 than Chicago did earlier in 2018. The photo on the left from the Chicago Tribune in 1967 reported that there were 8,116 total crime reports from March 2 to March 29, 1967. Compared to 2018, the Chicago Police Department stated that they had a total of 4,181 crime reports for the month of November in 2018. It should be noted that the amount of crimes could tend to be significantly different in spring than in fall, but generally when compared, the data above shows that crime in Chicago today is nearly half of what it was in 1967. The data above proves that the lack of trust in strangers in 2018 on the streets of Chicago may not be attributable to a higher crime rate, but rather an increased perception of it.

The increased perception of high crime rates in Chicago could possibly be a result of Donald Trump’s rhetoric about Chicago, or more broadly, conservative rhetoric as it relates to Chicago. For instance, a modern Chicago Tribune article from January 2, 2018 titled “Trump’s Misguided Ideas About Chicago Crime” makes the claim that Donald Trump continues to label Chicago as the “leader of the American carnage,” although there are smaller U.S. cities that have higher murder rates per capita than Chicago. Take Donald Trump’s rhetoric, his millions of devout followers who believe every word he says, and an increased accessibility to news at every corner of one’s life and you get a perfectly distorted vision of Chicago that many people falsely believe. The distorted vision that Chicago is a city riddled with crime at every corner is seemingly the only reason people need to be afraid of anything and everything unfamiliar that happens in the city, which in turn, would likely make it more difficult to perform such an inquiry into happiness in Chicago in 2018.

Photo Source: Chicago Tribune (Historic)

It would be great if we could blame the entire existence of a false perception of Chicago on one person right? Well, it’s not that simple. History is never simple. In fact, in the article above from the Chicago Tribune in 1960, the notion of a false perception of Chicago’s crime rate still existed. The false perception that Chicago is an incredibly dangerous city is not a new idea. The article above stated that “Chicago has a hard time living down its mistaken stigma” and that the author had lived in Chicago for 50 years and “never been burglarized.” The Chicago Tribune’s article shown above from 1960 proves that Chicago has been viewed as a dangerous city for at least 60 years.

Chicago’s notoriousness for being a dangerous city is not new. Looking at the sources presented earlier in this blog, it is evident that the public’s view of Chicago in 1960 and 2018 are strikingly similar. One thing discussed in this class was how often historians forget to consider how things have stayed the same, rather than just the ways things have changed. In the film “Inquiring Nuns,” Sister Arné and Sister Campion’s “are you happy” experiment demonstrated the willingness of people on the streets of Chicago to answer the question of a complete stranger before knowing what the purpose was (For the record, I am indeed aware of the possibility that people may have been more inclined to respond because the experiment was led by nuns, but this was not my focus). When considering how things have changed, it is important to consider how they have stayed the same, and the current state of Chicago is no exception.

Photo Source: Spencer Bailey

Photo Source: Spencer Bailey